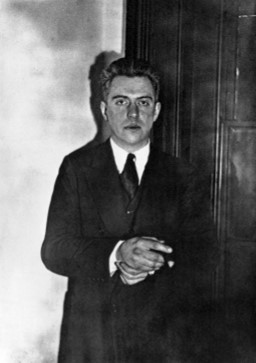

Early Life

Hart Crane is considered a pivotal even prophetic figure in American literature; he is often cast as a Romantic in the decades of high Modernism. Crane’s version of American Romanticism extended back through Walt Whitman to Ralph Waldo Emerson, and in his most ambitious work, The Bridge, he sought nothing less than an expression of the American experience in its entirety. As Allen Tate wrote in Essays of Four Decades, “Crane was one of those men whom every age seems to select as the spokesman of its spiritual life; they give the age away.” He was born in Garrettsville, Ohio, in 1899 to upper middle-class parents, with whom he had a fraught relationship. He was raised in part by his grandmother in Cleveland. His grandmother’s library was extensive, featuring editions of complete works by poets such as Victorian Robert Browning and Americans Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman, both of whom became major influences in Crane’s poetry. During his mid-teens Crane continued to read extensively, broadening his interests to include such writers as philosopher Plato, novelist Honore de Balzac, and Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Crane’s formal education, however, was continually undermined by family problems necessitating prolonged absences from school. Finally, in 1916, he left Cleveland without graduating and moved to New York City to attend Columbia University, which he hoped to enter upon passing an entrance examination.

New York City

Once in New York City, however, Crane abandoned college and began vigorously pursuing a literary career. Through a painter he knew earlier from Cleveland, Crane met other writers and gained exposure to various art movements and ideas. Crane read widely, including the works of French Symbolists Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud and contemporary Irishmen William Butler Yeats and James Joyce. Crane relied on his parents for financial support as well as selling advertising for the publication Little Review, which promoted the work of modernists such as Joyce and T. S. Eliot. During this time, Crane also associated with a far different periodical, Seven Arts, which devoted itself to traditional American literature extending from Nathaniel Hawthorne and Walt Whitman to Sherwood Anderson and Robert Frost. Both Seven Arts and Little Review exerted considerable influence on Crane, and in his own poetry he would seek to reconcile the two magazines’ disparate philosophies. At this time—around 1917—Crane was already producing publishable verse. Some of these works appeared in the local journal Pagan. Relatively short, Crane’s poems from this period reveal his interests in both tradition and experimentation, merging a rhyming structure with jarringly contemporary imagery. These early poems, though admired by some critics, were never held highly by Crane, and he never reprinted them in his lifetime.

Initially, Crane found New York City invigorating and even inspiring. But his parents divorced in 1917, and afterwards his mother and grandmother arrived to stay in his one-bedroom apartment. Bedridden from emotional exhaustion, Crane’s mother demanded his near constant attention. His problems mounted when his father, increasingly prosperous in the chocolate business, nonetheless threatened to withhold further funds until Crane found a job. To escape the pressures of family life, Crane attempted to enlist in the Army, only to be rejected as a minor. He then left New York City for Cleveland and found work in a munitions plant for the duration of World War I.

Postbellum

After the war, Crane stayed in Cleveland and found work as a reporter for the Cleveland Plain Dealer. He held that job only briefly, however, before returning to New York City to work once again for the Little Review. In mid-1919 his father used his influence in obtaining a position for his son as a shipping clerk. But Crane stayed at that job for only a few months before moving back to Ohio to work for his father’s own company. Their relationship was not congenial. Complicating matters further was the presence of Crane’s mother, with whom Crane had begun living after she returned to Cleveland. Tensions finally exploded in the spring of 1921 when Crane’s father criticized the son’s maternal ties, whereupon Crane apparently announced that he would no longer associate with his father. As biographer John Unterecker noted in Voyager: A Life of Hart Crane: “[Crane’s father] ... turned white with rage, shouting that if Hart didn’t apologize he would be disinherited. Hart climaxed the scene by screaming curses on his father and his father’s money.” The two men did not speak to each for the next two years. Upon leaving his father’s company, Crane stayed briefly in Cleveland working for advertising companies. He found similar work in New York City, but moving there hardly solved his ongoing personal problems. His mother continued to ply his sympathies by mail, regaling him with accounts of her emotional and physical troubles. Crane sought solace in sex but inevitably found heartbreak, for his infatuations with other men, including many sailors, went largely unreciprocated.

By 1922 Crane had already written many of the poems that would comprise his first collection, White Buildings. Among the most important of these verses is “Chaplinesque,” which he produced after viewing the great comic Charlie Chaplin’s film “The Kid.” In this poem Chaplin’s chief character—a fun-loving, mischievous tramp—represents the poet, whose own pursuit may be perceived as trivial but is nonetheless profound. For Crane, the film character’s optimism and sensitivity bears similarities to poets’ own outlooks toward adversity, and the tramp’s apparent disregard for his own persecution is indication of his innocence: “We will sidestep, and to the final smirk / Dally the doom of that inevitable thumb / That slowly chafes its puckered index toward us, / Facing the dull squint with what innocence / And what surprise!” A kind of optimism is also present in Crane’s poem “For the Marriage of Faustus and Helen,” also written in the early 1920s. Setting the marriage in contemporary times—Faustus rides a streetcar, and Helen appears at a jazz club—the poem suggests that Faust represents the poet seeking ideal beauty, and Helen embodies that beauty. In the poem’s concluding section, Helen’s beauty encompasses the triumph of the times too, and Crane calls for recognition of the age as one in which the poetic imagination surpasses the despair of recent events, notably World War I: “Distinctly praise the years, whose volatile / Blamed bleeding hands extend and thresh the height / The imagination spans beyond despair, / Outpacing bargain, vocable and prayer.” The optimism expressed in such poems as “For the Marriage of Faustus and Helen” was hardly indicative of Crane’s emotional state at the time. Soon after completing the aforementioned poem in the spring of 1923, Crane moved back to New York City and found work at another advertising agency. He once again found the job tedious and unrewarding. Adding to his displeasure was the unwelcome tumult and cacophony of city occurrences—automobile traffic, street vendors, and endless waves of marching pedestrians—that corrupted his concentration and stifled his imagination. By autumn Crane feared that his anxiety would soon lead to a nervous breakdown and so fled the city for nearby Woodstock. There he reveled in the relative tranquility of the rural environment and enjoyed the company of a few close friends.

Voyages

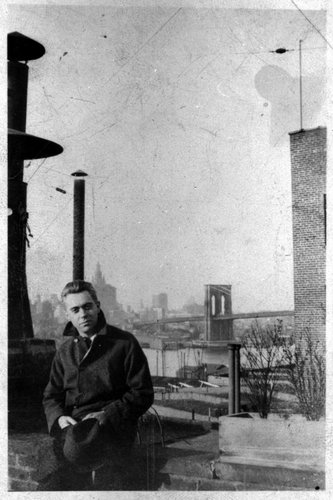

Once revived, Crane traveled back to New York City. Soon afterwards he fell in love with a sailor, Emil Opffer. Their relationship—one of intense sexual passion and occasional turbulence—inspired “Voyages,” a poetic sequence in praise of love. In Hart Crane, Quinn described this poem as “a celebration of the transforming power of love” and added that the work’s “metaphor is the sea, and its movement is from the lover’s dedication to a human and therefore changeable lover to a beloved beyond time and change.” Here the sea represents love in all its shifting complexity from calm to storm, and love, in turn, serves as the salvation of us all: “Bind us in time, O Season clear, and awe. / O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, / Bequeath us to no earthly shore until / Is answered in the vortex of our grave / The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise.” With its dazzling poeticism and mysteriously inspiring perspective, this poem is often hailed as Crane’s greatest achievement. R. W. B. Lewis, for instance, wrote in The Poetry of Hart Crane that the poem was Crane’s “lyrical masterpiece.” By the time he finished “Voyages“ in 1924, Crane had already commenced the first drafts of his ambitious poem The Bridge, which he intended, at least in part, as an alternative to T. S. Eliot’s bleak masterwork, The Waste Land. With this long poem, which eventually comprised fifteen sections and sixty pages, Crane sought to provide a panorama of what he called “the American experience.” Adopting the Brooklyn Bridge as the poem’s sustaining symbol, Crane celebrates, in often obscure imagery, various peoples and places—from explorer Christopher Columbus and the legendary Rip Van Winkle to the contemporary New England landscape and the East River tunnel. The bridge, in turn, serves as the structure uniting, and representing, America. In addition, it functions as the embodiment of uniquely American optimism and serves as a source of inspiration and patriotic devotion: “O Sleepless as the river under thee, / Vaulting the sea, the prairies’ dreaming sod, / Unto us lowliest sometime sweep, descend / And of the curveship lend a myth to God.”

White Buildings/The Bridge

In 1926, while Crane worked on The Bridge, his verse collection White Buildings was published. This work earned him substantial respect as an imposing stylist, one whose lyricism and imagery recalled the French Romantics Baudelaire and Rimbaud. But it prompted speculation that Crane was an imprecise and confused artist, one who sometimes settled for sound instead of sense. Edmund Wilson, for instance, wrote in New Republic that “though [Crane] can sometimes move us, the emotion is oddly vague.” For Wilson, whose essay was later reprinted in The Shores of Light, Crane possessed “a style that is strikingly original—almost something like a great style, if there could be such a thing as a great style which was ... not ... applied to any subject at all.” Crane, for his part, responded to similar charges from Poetry editor Harriet Monroe by claiming that his poetry is consistent with the illogicality of the genre. “It all comes to the recognition,” he declared, “that emotional dynamics are not to be confused with any absolute order of rationalized definitions; ergo, in poetry the rationale of metaphor belongs to another order of experience than science, and is not to be limited by a scientific and arbitrary code or relationships either in verbal inflections or concepts.” By the time that White Buildings appeared in print, Crane’s intense relationship with Opffer had faded. Crane again alternated from euphoria to depression, seeking solace in alcohol and sexual encounters. Constant conflict with his mother further aggravated his despair, as did the death of his grandmother in 1928. More positively, Crane realized a reconciliation with his father around that time, but the parent’s death soon afterward only served to plunge the poet once more into depression.

Europe/Mexico

With his inheritance, Crane fled his mother and traveled to Europe. There he associated with prominent figures in Paris’s American expatriate community, notably publisher and poet Harry Crosby, who murdered his mistress and killed himself the following year. Crane wrote little in Europe and when he returned to the United States he continued a pattern of self-destructive behaviors. Furthermore, his self-confidence was shaken by the disappointing reception accorded The Bridge by critics, many of whom expressed respect for his effort but dissatisfaction with his achievement. But even critics that deemed Crane’s work a failure readily expressed respect for his creative undertaking. William Rose Benet, for instance, declared in the Saturday Review of Literature that Crane had “failed in creating what might have been a truly great poem.” But Benet nonetheless deemed The Bridge “fascinating” and declared that it “reveals potencies in the author that may make his next work even more remarkable.” Crane, however, had entered a creative slump from which he would not recover. He applied for a Guggenheim fellowship with intentions of studying European culture and the American poetic sensibility. After obtaining the fellowship, though, Crane traveled to Mexico. At this time he also experienced a heterosexual romance—presumably his only one—with Peggy Baird, who was then married to prominent literary figure Malcolm Cowley. Crane wrote only infrequently, and he seemed to have felt that his poems confirmed his fears that his talent had declined significantly. Finally, in 1932, his despair turned all-consuming, and on April 27, while traveling by ship with Baird, Crane killed himself by leaping into the Gulf of Mexico.

Postscript

Crane has received critical reevaluation in the last decades. In the years immediately after his death, Crane’s reputation was as a failed Romantic poet. Allen Tate, writing in his Essays of Four Decades, assessed Crane’s artistic achievement as an admirable, but unavoidable, failure. Tate noted that Crane, like the earlier Romantics, attempted the overwhelming imposition of his own will in his poetry, and in so doing reached the point at which his will, and thus his art, became self-reflexive, and thus self-destructive. “By attempting an extreme solution to the romantic problem,” Tate contended, “Crane proved that it cannot be solved.” New Critics like Tate and R.P. Blakmur tended to focus on Crane’s “failures” and “imperfections,” often declaring him “obscure.” In the 1970s and ‘80s, scholars working in queer theory rediscovered Crane as an exemplary outsider whose intense, opaque metaphors revealed cultural and historical conditions of queer life. For scholars such as Tim Dean, Crane’s hermetic language subverted binaries governing sexual and psychological life by generating modes of privacy at odds with “the closet,” a social system in which sexual identification determined how and where one circulated. For Dean and other critics who see Crane’s queerness as inextricable from his work’s density, Crane’s poetry shows, in Dean’s words, the “potential of poetic forms to alter ostensibly hegemonic constructions of sexuality and subjectivity.”